Writing Lessons from Leonardo: Taking the Road Less Traveled

This post also appears on The MFA Project, an online resource for writers seeking educational alternatives to a degree in creative writing.

Perhaps it’s that I’m preparing to set out on the great American road trip – the first in my life, as it happens – or roads just keep appearing all over the place in my poems, prompting me to wonder whether I’ve developed some kind of unconscious obsession with the romance of wandering, pursuing wide open spaces, and getting lost. But of late, roads and the mythical journey they represent have come to figure large in my thinking about writing and my approach to a writing education. And not just any roads, but the abandoned ones, the neglected ones, or the ones most people don’t seem to be taking at all. It’s not even that I am on such a road myself at the moment, but the topic for whatever reason intrigues me, like a terrier after a scent. And I find myself rooting around in it.

This is where I warn you that my findings are irreverently and unreservedly self-serving, contrarian, and anti-creative writing MFA. What do they call it in psychology, confirmation bias?

I owe Maria Popova and her Brain Pickings blog at least three years’ worth of gratitude and homemade pies for all the wisdom that’s come my way via her gleanings from the world of literature, covering every arts/sciences discipline and topic imaginable. One of her latest posts, entitled “Leonardo’s Brain: What a Posthumous Brain Scan Six Centuries Later Reveals about the Source of da Vinci’s Creativity,” snagged my attention earlier this week and wouldn’t let go.

Here’s what I pulled from the post that I found pertinent to the above.

The road less traveled

Owing to his illegitimate birth, Leonardo apparently didn’t have a formal education. Banned from the liturgical schools of his time, he was entirely self-taught in Greek and Latin, the languages of the Italian Renaissance that were the portal he would later access to become the mathematician, artist, and scientist that history remembers. Long after he had established his career, people questioned his expertise numerous times on the point that he lacked the 16th century equivalent of what would have been a college degree.

His reply?

They will say that because of my lack of book learning, I cannot properly express what I desire to treat of. Do they not know that my subjects require for their exposition experience rather than the words of others? And since experience has been the mistress, to her in all points I make my appeal.

Experience as mistress? Is he saying that the hours spent reading and writing at my desk is experience enough without an advanced degree? That I’m getting the “book learning” he too missed back in his day, by reading writers I admire, analyzing their works and seeing how they do it, which is maybe an education in its right? These are genuine questions, but that’s the drift I got from it.

Zigging where everyone else zags

As if a scrappy upbringing and entry into the learned aristocracy weren’t hard enough, Leonardo challenged himself by doing most things backwards. Modern scans of his brain reveal an unusually thick corpus callosum, the portion of the brain that acts as a bridge between its left and right hemispheres. It’s speculated that this feature of his anatomy was due in part to the daily exercise he underwent using all parts of his mind.

Brain Pickings on his habits when it came to his writing:

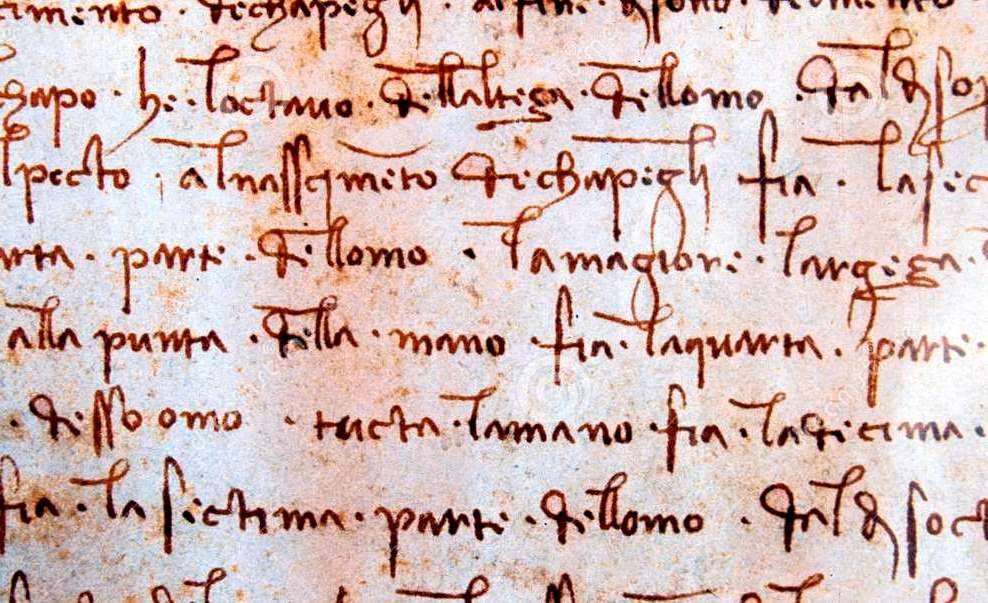

Someone wishing to read Leonardo’s manuscripts must first hold the pages before a mirror. Instead of writing from left to right, which is the standard among all European languages, he chose to write from right to left — what the rest of us would consider backward writing. And he used his left hand to write.

Reading this, I was reminded of the advice we often hear, to do something new every day, which I’m beginning to think is a watered-down version of the principle he demonstrated with this habit. Reading about Leonardo’s handwriting got me thinking how de-routinizing our lives, shaking things up, challenging ourselves to see the world with new eyes, can enrich our minds and our creative process. This was part of his self-education, and it required tremendous effort and discipline, the kind that no one could exert over Leonardo’s learning except himself. And it was attended by a child-like curiosity that was endless.

Just one look at his notebooks, and you can see the full fruition of this habit. It’s a thing of wonder.

The pursuit of truth

In the end, though, we cannot escape the reality that some just enter the world that way, as geniuses. Leonardo da Vinci was indisputably one of them. People like him won the genetic lottery; we say, or they got lucky or had the right opportunities. Seeing such extreme talent, we can be tempted to slam the notebook shut or dump the brush and canvas and paint in the trash, saying, “I could never be as good as so-and-so. I’m done.”

Simone Weil, turn-of-the-century mystic and writer, had this to say to those despairers:

“After months of inward darkness, I suddenly had the everlasting conviction that any human being, even though practically devoid of natural faculties, can penetrate to the kingdom of truth reserved for genius, if only he longs for truth and perpetually concentrates all his attention upon its attainment. He thus becomes a genius too, even though for lack of talent his genius cannot be visible from outside.”

And that truth, as I see and understand it, is the story only we as individuals can tell, because it’s the song we were born to sing, and how could that not be the point and culmination of truth?

If that seems small consolation for those burning with a desire for creative attainment, I can offer this fun video about how hard Leonardo actually had to work to achieve mastery at his craft.

I can also offer several memories I love to dredge up and hold to my heart whenever I get cold and afraid of the dark, a sensation we all experience, lonely at the desk with nothing but stories in our heads and wondering who will ever care. The first is a man, and the second is a group of people on a stage.

In February of last year, I had just lost a beloved relative and was in a deep state of grieving. To pull me out of my funk my husband took me into Seattle, where we stayed in a hostel, watched the Chinese Lunar New Year celebrations, and ate some of the best food I’d had in a long time. The weekend couldn’t have been more perfect, but it wasn’t over yet. As Phil and I made our way towards the water in the waning light of the plaza at Westlake Center, we were stopped in our tracks by a man playing his electric violin.

His name was Pasquale Santos and I’ll never forget him. His music, a song I later recognized as Train’s “Soul Sister”, was achingly gorgeous. But I was also spellbound by the way he moved his body as he played, and how he smiled. Everything about his presence said, I love doing this and I don’t care about anything else. Not about the attention or praise of others, though he received plenty of that (including from me as I gushed how much I loved his music and dropped a ten in his violin case), and certainly not about money, but because music to him was like breathing, and he couldn’t see living his life without it. Watch the video and see it in his face.

The second of my fondest memories was in late high school, when I attended a play at Seattle’s Intiman Theater with my brother called The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Thinking back on it, I remember nothing about the details of the play, the plot, the characters. I hardly even remember the stage or costumes, though I remember a spinning platform that had the audience in stitches and that the costumes were deliriously colorful. What I remember of that night was the deep emotion I felt as the play revealed the gears and pinions of a mind joyfully at work, humming along, satisfied in its complete absorption with and love of the object of its passion.

The game and the road are long, and I’m finding the only way to play the game and walk the road without going crazy is to be patient, stay curious and awake to the wonder of the world, and remain faithful to the truth that’s mine to live. – Hannah

In the coming weeks, we will be gathering interviews with a fun lineup of authors with their thoughts and insights on writing craft and the writing life. Stay tuned.