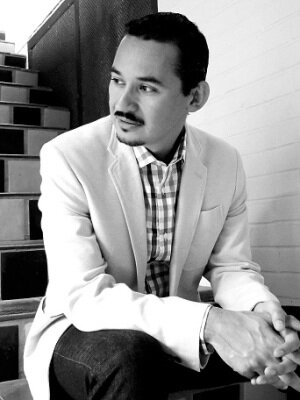

Niel Rosenthalis

Niel Rosenthalis

I recently met Niel Rosenthalis at AWP in Los Angeles at the Deadly Chaps Press booth, by chance after missing an author signing (something that seems to happen to me a lot at these kinds of events). We got to talking about poetry and agreed to keep in touch. He wrote me after the conference offering to help out with Primal School, and the more we spoke and I got to know his work, the more honored and grateful I felt for having met this force of a poet. I’ll let the interview serve as proof, but I’ll add that just this week, Niel has been offered the Third Year Fellowship in Poetry at Washington University in St. Louis. — HLJ

===

In your recent interview with Joanna Valente for Luna Luna, you described how in writing your first chapbook collection, TRY ME, you saw “trees, grammar, the mechanical goings-on, etc. as […] a struggle with each other.” That struggle interests me as a reader of your poems; could you tell us more about it?

In that interview I think I was making a point about how I don’t distinguish, really, between the mechanical and the natural, and how that group of nouns came from the process of writing via erasures — mostly of nonfiction books and novels. ERASURE is the practice of making a new text out of an existing one. You look at a text, say, an article or a novel, and you decide to whiten out all the words you don't want, so you're left with the words you do want – and the idea, for me, is to make a poem out of those words. Basically, it's like an enormous ready-made word bank.

In the way that I use erasure (other poets use it very differently), the poems sound the same as poems I might write without erasure. My subjectivity shows through whatever I do. Sometimes the process exposes me to new words that excite me in a new way, and sometimes I use the words I would use anyway, but because I’m working within this formal restriction, only using the words before me, something in me is reoriented. Trees, grammar and the mechanics of the way things work form a part of my Image Bank, I guess — which I’d define as that group of images I find myself obsessed with. Every poet has an Image Bank. And out of this bank, I try to work out whatever is agitating me about my perception of experience.

So I take you keep a notebook to aid in storing that Image Bank? Or do these images come to you in your writing, like a daydream?

Good question – I keep a notebook and write pretty often. Sometimes I sit in a public place and just observe what I see. I take notes when I'm reading poems, essays, scientific articles, books on the history of ancient Rome (or whatever it is I'm doing – I read pretty widely and sometimes deeply and sometimes not, haha). I copy down great sentences and wonder how they work — what makes them pleasurable to me, and so on. I find that I do have a set group of words that comes to me when I’m just free-writing, and so just to push myself, sometimes I'll open up a book (say a book of poems or a random nonfiction book I have laying around the house), and pick ten words that really stand out to me just because I like them. They don't have to be especially complicated, they just need to excite me. For instance, if I turn to the word bank I started recently, I see the words: extension, forward, expanse, proof, rapprochement. I don't think I finished building that bank, but sometimes when writing I say, “Okay, let me see if I can get that word into the poem because I like how it sounds.” I don't have to keep the word, but if it gets me excited on the page, it can generate a few lines that do work well (and often I'll have to go back and cut the word I pulled from the image bank because the line it was in didn't end up working). Which isn't to say the Image Bank makes or breaks a poem! What really makes a poem exciting to me is the tension in it – and poets have different ways of generating this tension. Some use really elaborate syntax, i.e. the way the words in a sentence or a line come together over time. Others simply have a funky Image Bank. Still others prioritize using the page as a kind of field, skipping around and building arrangements of words that challenge one’s sense of how one word follows another. And all poets use some combination of these three tension-generators, because syntax, word choice, and page space all can be manipulated. They form the technical stuff of which poems are made.

Affirming to know I’m not the only one who approaches writing in this way; seeing what words call to me in my reading and finding a home for them in my poems . So many poems are really just houses built of stolen lines, words, ideas… there’s nothing contraband about it when you’ve made something new out of them. And your playfulness with syntax does intrigue me, so let’s talk about “Placed.” Fascinating story behind it: you say the poem was cut from 40+ pages of observation in a time and location? Tell us about that process.

===

PLACED

An Intersection

I was sitting at a table outside in the night. The people around me ate and drank in comfort, a few notches below bliss. What else is hammered. Watch your tone. I can’t, it’s like the back of my head.

One house lit-up with a birthday banner

in the foyer; the sneezing dogs on their

evening out; a semi-present wish

to stop all this.

Some people pose for a picture. “Wait, guys, let’s get one of us laughing at each other.” Laughter is a form of what kind of thinking. What’s worse: the people or the reclamation of want the people bring out in you.

I kid myself.

I say, “I like my sweetstop tongue.”

I can’t look

to be a part of all this.

An Exchange

On a tour of the city, I was hit by the sight of white dahlias (“Always place description in the present tense.”)

The dahlias were in a toss from last night’s flash flood. The hill they were planted on made them lean. And then I remembered what it was like to see something for the first time.

“What would it look like?”

— A woman with a braid down her back, to her friend at the café.

“I wanted to know what a poodle cut looks like on a person, a kind of mullet…with a tight bun at the back.”

Pausing to fill in, one said, “Well at least it will grow back,” to which (he’d missed the point) she said, “no, no, it was great, glad we did it.”

Be absorbed by minutiae.

He’s aside of this now so if he wants to leave he can leave without walking through a door.

A Separation

The couple in green sat at the table with fries, which their hands went to, then to their mouths, then down to their laps. At times one went for it while the other waited, or both went, or neither. One touched the other’s knee. The other had arms closed together and turned her head this way and that. What they were was how they were. To that end, I watched from my box. (Around me the people sat in theirs such that they could look at or to the street, where the people passed.) Pass the salt, please. One did.

Keegan Lester

Keegan Lester